中国日报网·网站 2026-01-14 16:50:59

A vlogger couple uses one-minute videos to trace dish origins and showcase the culinary heritage of China's ethnic groups.

Why do Chinese people eat dumplings during the winter solstice? Was egg-fried rice once considered a dish reserved for emperors?

The answers to these questions can be found in the videos of "Jiangxiaojin" on Douyin (the Chinese version of TikTok). Created by 32-year-old Jiang Jin and her husband, Chen Jili, these one-minute videos delve into the fascinating stories behind everyday Chinese dishes.

So far, the couple's videos have garnered over 400,000 followers, mostly aged between 24 and 40.

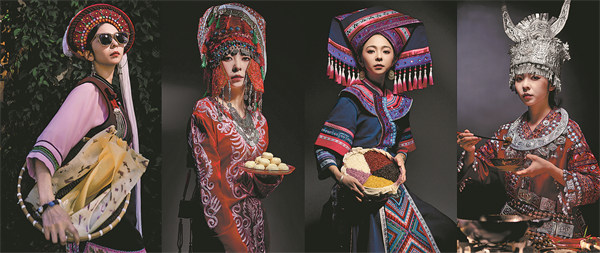

One of their most popular series focuses on the diverse food cultures of China's 56 ethnic groups. Since its launch in mid-2024, the couple has introduced snacks from 25 different groups. Each episode begins with a dramatized reenactment of the dish's origin and ends with a display of traditional attire and the completed dish.

"We're not just explaining how these foods came to be,"Chen said. "We also hope to highlight the history and traditions of each ethnic group through their cuisine."

In their latest series, released in December, one video about the Kirgiz people of Xinjiang condenses a thousand years of history into just a minute. It traces their ancestors' allegiance to the Tang Dynasty (618-907), their role in defending the Pamir Plateau during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), and the 1964 story of Bruhamhan Maoldou, a 19-year-old border guard who spent 60 years carving over 100,000 stones along the frontier — each engraved with the word "China" — as silent markers of the nation's boundaries.

The video concludes by introducing naigeda, a traditional Kirgiz snack made of dried dairy. Lightweight and long-lasting, it once served as a vital ration for those stationed in the resource-poor highlands.

"The history of the Kirgiz people is not widely known," Chen said. "But this video sparked meaningful discussions among viewers."

It has already received more than 31,000 likes.

Cuisine chronicles

Without any prior social media experience, Jiang first considered becoming a video content creator out of a deep curiosity about food. Growing up in Sichuan, a region celebrated for its culinary traditions, she used to spend weekends exploring back alleys and side streets, sampling local snacks. But more than recipes or flavors, what fascinated her were the stories behind each dish.

"Sichuan has a long history of migration," Jiang explained. "That's why so many dishes here carry influences from Guangdong and Hubei."

Unlike most food vloggers, Jiang and Chen begin their work in the library, not the kitchen. For each video, they spend three to five days researching, followed by another two to three days writing the script.

One of their biggest challenges is verifying sources. When researching dumplings, for example, they repeatedly came across the popular claim that dumplings were invented by Zhang Zhongjing, a renowned physician of the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220).

"But that doesn't really hold up," Jiang said. "Similar foods were already documented in the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD24)."

After reviewing historical records, Jiang and Chen concluded that wrapping fillings in dough likely emerged gradually as a practical winter habit — especially when cooking fuel was scarce, and people needed a more efficient way to prepare meals. Over time, this everyday practice took on cultural meaning and became tied to seasonal rituals, eventually evolving into the tradition of eating dumplings during the winter solstice.

"Every dish has its own roots — it doesn't just appear out of nowhere," Jiang said."Each food has a developmental lineage, and its story is shaped by social change. That's why we always assess the plausibility of its origins in historical context."

In addition to consulting ethnographies and local chronicles, Jiang and Chen also explore culinary origins through the evolution of Chinese characters.

For example, when investigating the Qiang ethnic group's larou, a type of cured meat, they were initially puzzled by the tradition of smoking meat in the 12th month of the lunar calendar.

Their breakthrough came when they discovered that the character la is a variant of lie, meaning "to hunt". During the Shang and Zhou dynasties (c.16th century-256 BC), people hunted in the 12th lunar month for ancestor worship. Meat prepared for these rituals was called lierou. After the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC) standardized the writing system, the term gradually evolved into larou.

"We were thrilled when we uncovered the truth," Jiang said. "Tracing an origin like that is incredibly satisfying."

To ensure accuracy, Jiang and Chen also ground their research in firsthand observation. During a field trip to Yunnan, they learned that the Bai ethnic group's rushan — a deep-fried sheet of milk curd — dates back to the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368). At the time, Mongol rulers introduced new dairy-production techniques, which later merged with the Bai people's traditional fermentation practices to create this unique snack.

"Many ethnic foods resemble one another, but each still preserves its own cultural roots. This diversity — alongside unity — shows how different groups migrated, integrated, and evolved across China," Jiang explained.

Chen recalled a message from a follower in Malaysia who shared their family's migration story: their ancestors moved from Fujian to Malaysia and later developed the beloved dish bak kut teh, an herbal pork soup. "The cultural traces carried through food can be found all over the world," Jiang reflected.

She added that her journey into food history videos was strongly influenced by Chen, who has long been fascinated by how Chinese society — and Chinese businesses in particular — have evolved over time. Through him, she began to see everyday things like food not just as something people eat, but as a record of cultural change and continuity.

"He planted a seed of pride in our culture in my heart," Jiang said. "What we're doing now is passing that feeling on to others — and hopefully, one day, it will bloom and spread."

责编:田梦瑶

一审:田梦瑶

二审:秦慧英

三审:张权

来源:中国日报网·网站

我要问

下载APP

下载APP 报料

报料 关于

关于

湘公网安备 43010502000374号

湘公网安备 43010502000374号